dudley

Click for full resolution image

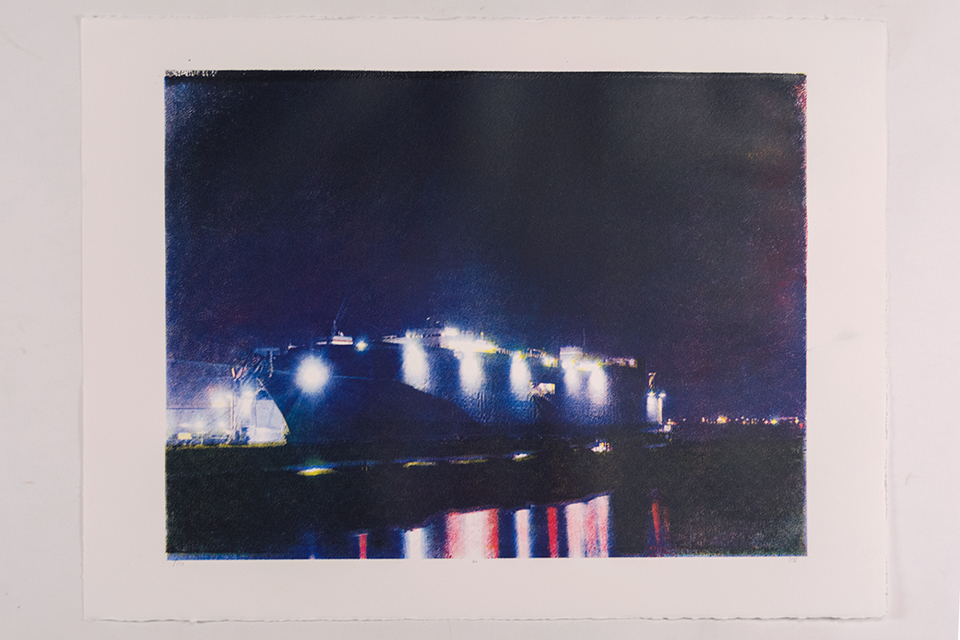

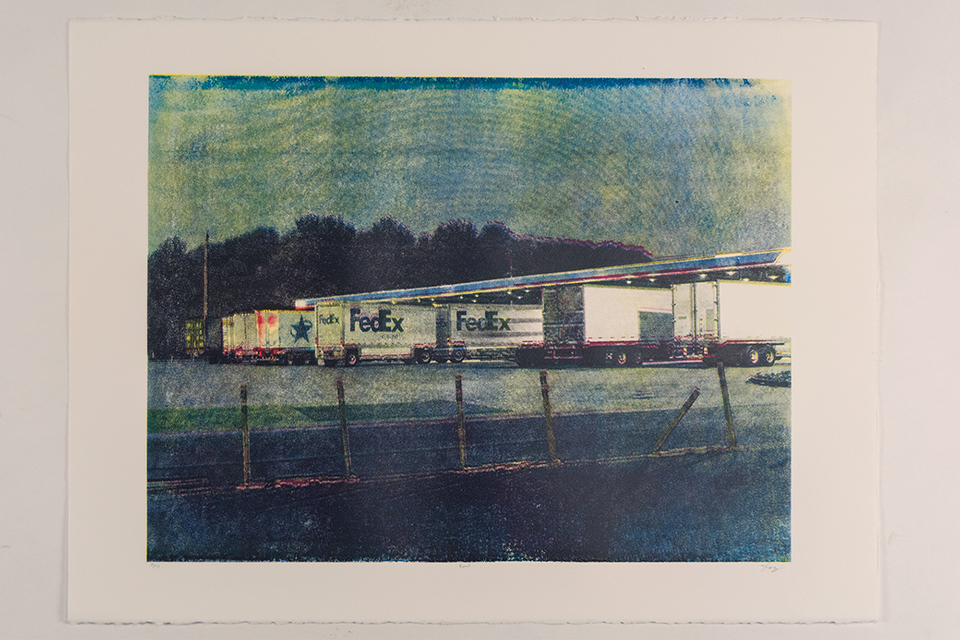

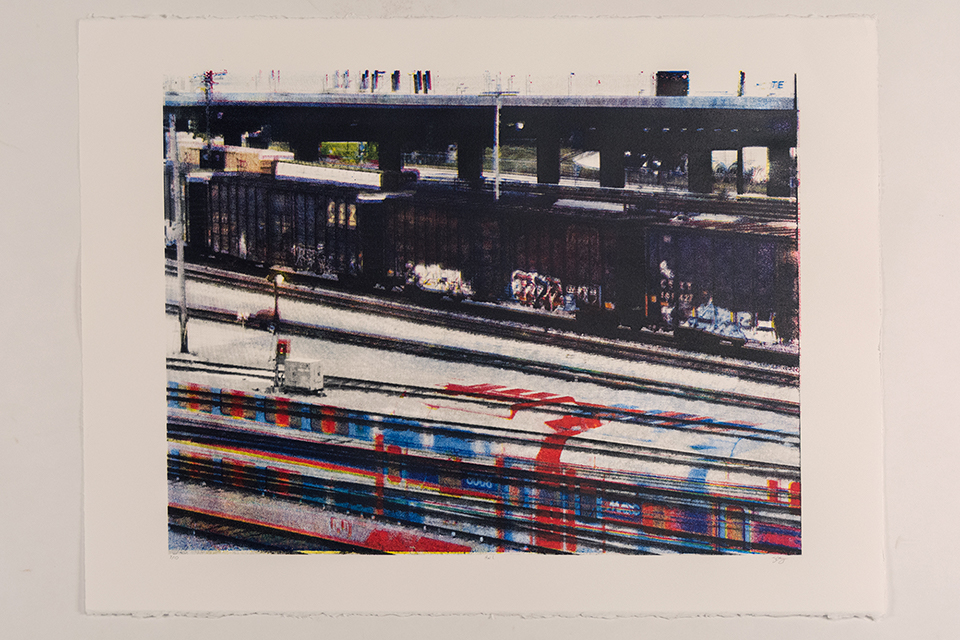

CHANNELS (КАНАЛЫ) is a piece in multiple mediums inspired by the work of Russian photochemist Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky, who developed a method of color photography using black-and-white film and color filters decades before color film became commercially available. The process imitates how the human eye senses color by separating light into the red, green, and blue color channels, in much the same way a television or computer screen reproduces full-color images by alternating red, green, and blue pixels. The trick here, though, was that the images were taken one after another, switching colors between each exposure, while the camera sat, stationary, on a tripod. Although his methods were intended to produce seamless, full-color photographs (which they primarily did), the limitations of the medium meant that any changes that occurred between the exposures would create ghosts where the colors mismatched. This same error in registration can be seen in the iconic purple and green halos of old cathode tube televisions and is a popular visual trope in screenprinted t-shirts and other graphic media.

When I first saw Gorsky’s series Photographs for the Tzar, the records of his trans-Russian documentary trip by rail funded and outfitted by Nicholas II, I fell in love with, above all else, the artifacts and ‘glitches’ inherent in the work. While most of the images were simply luscious landscapes and cityscapes with a liminal, otherworldly vibe (thanks to the slight offsets of each color), every now and again there would be movement enough in the frame for that subtle shimmer to jump front and center, putting the process on display as much as the intended subject. In one particular image, nestled among stoic women carrying picker’s baskets, a young Georgian harvest girl broke character between exposures, trying her best to stifle a laugh, and it was caught on camera as a rainbow of smiling silhouettes. It was at this moment I realized that this process could be used as a framework for exploring color as a method of expressing time and movement.

While Gorsky had originally set out to remove all traces of process from his work so as to ‘accurately portray the world,’ I made it my goal to expose the methods by which the composites were made and bring to light the very artifacts that I fell in love with in the first place. To replicate Gorsky’s process, I captured each of the images in the series on a medium-format film camera with colored lighting gels to split the color channels for each exposure. After developing my film, I scanned the negatives and digitally composited the red, green, and blue frames into full-color RGB images. My subjects were chosen, much like my process, as the pieces which incidentally worked their way into Gorsky’s photo-documentation of Russia. Though he had been sent to chronicle the sleepy villages of his nation, his travels by railcar led him through the most industrial portions of Russia, as those were the first regions to gain rail access at the time. While not his intention, Sergei Gorsky had, in fact, archived the channels of Russian industry at the turn of the century.

Having successfully created composited RGB images via the three-color process, I found myself with a bit of a dilemma. Originally, in the early 1900’s, these photos would be viewed using a photochromoscope, a device made of reflectors and a new set of red, green, and blue color filters to project the images to the eye when held up to the light. It was, in essence, an analog version of an additive color RGB monitor. To print this sort of image, though, the frames had to be inverted and re-synthesized with subtractive color theory: replacing red, green, and blue with cyan, magenta, yellow, and black. Rather than simply modifying the images digitally for offset printing, I worked from the negatives to create new composites which I then used as the basis for exposing a series of silkscreens to use as a method of analog fine art printing. The resulting edition of ten sets of 18x24in four-color impressions serves as manually-registered, hand-squeegeed evidence of several hundred hours in the pursuit of photographic prints that could not have been achieved by any other means.

When I first saw Gorsky’s series Photographs for the Tzar, the records of his trans-Russian documentary trip by rail funded and outfitted by Nicholas II, I fell in love with, above all else, the artifacts and ‘glitches’ inherent in the work. While most of the images were simply luscious landscapes and cityscapes with a liminal, otherworldly vibe (thanks to the slight offsets of each color), every now and again there would be movement enough in the frame for that subtle shimmer to jump front and center, putting the process on display as much as the intended subject. In one particular image, nestled among stoic women carrying picker’s baskets, a young Georgian harvest girl broke character between exposures, trying her best to stifle a laugh, and it was caught on camera as a rainbow of smiling silhouettes. It was at this moment I realized that this process could be used as a framework for exploring color as a method of expressing time and movement.

While Gorsky had originally set out to remove all traces of process from his work so as to ‘accurately portray the world,’ I made it my goal to expose the methods by which the composites were made and bring to light the very artifacts that I fell in love with in the first place. To replicate Gorsky’s process, I captured each of the images in the series on a medium-format film camera with colored lighting gels to split the color channels for each exposure. After developing my film, I scanned the negatives and digitally composited the red, green, and blue frames into full-color RGB images. My subjects were chosen, much like my process, as the pieces which incidentally worked their way into Gorsky’s photo-documentation of Russia. Though he had been sent to chronicle the sleepy villages of his nation, his travels by railcar led him through the most industrial portions of Russia, as those were the first regions to gain rail access at the time. While not his intention, Sergei Gorsky had, in fact, archived the channels of Russian industry at the turn of the century.

Having successfully created composited RGB images via the three-color process, I found myself with a bit of a dilemma. Originally, in the early 1900’s, these photos would be viewed using a photochromoscope, a device made of reflectors and a new set of red, green, and blue color filters to project the images to the eye when held up to the light. It was, in essence, an analog version of an additive color RGB monitor. To print this sort of image, though, the frames had to be inverted and re-synthesized with subtractive color theory: replacing red, green, and blue with cyan, magenta, yellow, and black. Rather than simply modifying the images digitally for offset printing, I worked from the negatives to create new composites which I then used as the basis for exposing a series of silkscreens to use as a method of analog fine art printing. The resulting edition of ten sets of 18x24in four-color impressions serves as manually-registered, hand-squeegeed evidence of several hundred hours in the pursuit of photographic prints that could not have been achieved by any other means.